Where AI Interventions Succeed or Fail

This work was supported through the AI4D project Advancing Responsible AI: Evaluating AI4D Investments for Impact and Equity and was originally published on the IDinsight website

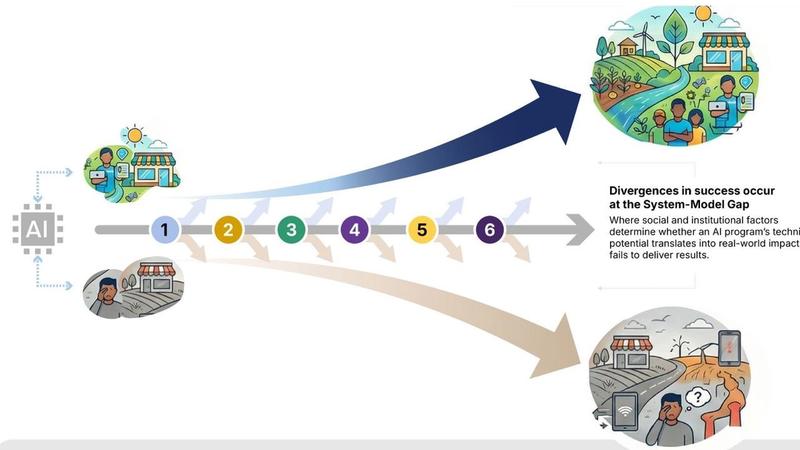

Inflection points in the model-practice gap

The story begins in Kenya where small and medium size business owners were given access to an “AI mentor” through WhatsApp. The idea was simple: offer personalized business advice, at scale, to people who normally have little or no access to quality support. It was low-cost, easy to deploy, and full of promise (Otis et al. 2025).

However, the impacts were anything but straightforward. The same tool, with the same design and underlying model, produced radically different outcomes depending on the user. The financial impact on entrepreneurs varied significantly: those already performing well experienced a roughly 20% increase in both revenues and profits, while struggling businesses saw a 10% decline in theirs.

This was not a failure of algorithms or a flaw in model performance. The advice was not obviously wrong. The divergence emerged in the space between the technology and its users, the space where lived realities, constraints, capabilities, and opportunities interact with the system. In those encounters, the trajectory of the intervention shifted.

The Model-Practice Gap

Most of the hype around AI comes from its technical proficiency. Early narratives fixate on the data pipeline, the capabilities and accuracy of the latest model, and performance benchmarks. This is understandable: when outcomes are uncertain, attention tends to concentrate on what the system can do in principle. We debate potential upsides and risks, celebrate accuracy improvements, and worry about catastrophic failures, often drawing on high-profile cases where poor model performance caused real harm (e.g., Angwin et al. 2016; Haven 2020; Gebru et al. 2021; NTSB 2020).

The focus remains largely at the level of affordances, understood as the apparent action possibilities a system is designed to unlock (Gaver 1991; C. Anderson & Robbey 2017), such as translation or large-scale summarization. From there, we routinely over-extrapolate, inferring societal benefits and risks from controlled demonstrations rather than from how models perform in real-world contexts (Narayanan & Kapoor 2024).

Between model capabilities and real-world outcomes sits the model–practice gap: the set of social and institutional processes through which technical affordances encounter human use. These processes determine whether technological potential converts into meaningful outcomes or quietly dissipates.

This insight is not new. Research across multiple fields shows that users reinterpret, negotiate, routinize, or ignore technologies rather than adopting them wholesale (Pinch & Bijker 1984; MacKenzie & Wajcman 1985; Akrich 1992; Suchman 1987). ICT4D research highlights the role of intermediaries, organizations, and conversion factors (Madon 2000; Heeks 2002; Avgerou 2010). Studies of improvisation and enactment show how meaningful use emerges through adaptation, bricolage, and situated practice (Ciborra 1999; Orlikowski 2000). Classic work on the diffusion of technology highlights the decisive role of norms, peer influence, and social networks (Rogers 2003). Across these literatures, the conclusion is consistent: technical provision can be impactful, but its trajectory is determined by the social, cultural, and institutional dynamics through which people make technologies usable and consequential.

Despite rhetoric promising transformation, AI today operates as a “normal technology”, bound by the institutional and material contexts that organize its use (Narayanan & Kapoor 2025). Studies of real-world adoption consistently find muted or disappointing results (Economist 2025; Deloitte 2025; McKinsey 2025; MIT 2025). The gap between technical capability and realized impact is wide and persistent. Understanding that gap requires identifying the inflection points where trajectories diverge.

Inflection Points in the Model–Practice Gap

AI-for-development interventions succeed or fail not because of the model alone, but because of a series of socio-technical inflection points where access, comprehension, trust, relevance, motivation, and opportunity meet users’ actual conditions. At each inflection point, the trajectory of an intervention can gain momentum, lose steam, or slip into negative territory. Different users move through these points in different ways, which is why identical systems generate divergent outcomes.

Drawing from the literature, practitioner insights, and emerging evaluation evidence, we outline six inflection points that collectively determine the shape and direction of AI-for-development outcomes.

Access and interaction. “How and to what extent can people access and use the intervention” This is the first inflection point. If users cannot access the system or cannot use it effectively, the trajectory ends before it begins. Practical, social, and economic access conditions (location, timing, affordability, norms, alignment with existing practices) must align with interaction quality (interface clarity, usability, accessibility, latency, device and bandwidth constraints, error recovery). If either side fails, downstream effects are irrelevant.

Comprehension. “How do people make sense of the information being presented?” Accurate information can still fail if it is unintelligible. Low levels of literacy, mismatched language, unfamiliar units, technical jargon, or culturally inappropriate phrasing can make correct information unusable. The trajectory bends here: comprehension is necessary for any further effect.

Legitimacy. “To what extent do people judge the source and the message as legitimate, and why?” Even clear messages cannot drive behavior if trust collapses. Legitimacy is contextual and relational, built over time and easily damaged. A single confidently wrong output can close this inflection point entirely.

Knowledge. “How does the intervention connect to people’s realities and understandings in ways that are appropriate and actionable?” Users may understand information yet find it irrelevant or impractical. Whether information becomes actionable knowledge depends on timeliness, cognitive load, familiarity, and alignment with lived experience. It’s the difference between “I understand this” and “I can work with this.”

Motivation. “Does the intervention align with people’s lived realities, mental models, socio-cultural norms and behavioral predispositions in a way that motivates them to act?” Understanding and trust still need to translate into internal willingness to act. Motivation depends on how advice fits with people’s mental models, emotions, social expectations, and daily constraints. The trajectory can stall here even when upstream conditions hold.

Opportunity. “Do people have the means and opportunity to convert their understanding and motivation into action?” Even motivated users may lack the material, institutional, or infrastructural means to act. Opportunity conversion depends on resources, organizational processes, and agency. Without these, good guidance becomes inert.

If an intervention fails at any of these inflection points for a given group, the outcome trajectory bends differently for that group. This is why the same system can amplify capability for some users while magnifying disadvantage for others. This pattern reflects what Toyama (2011) describes as technology’s tendency to magnify underlying human and institutional strengths and weaknesses.

Where Trajectories Diverged

For higher-performing entrepreneurs in Kenya, each inflection point tilted in a positive direction. The advice was intelligible, credible, and matched their existing skills, capital, and networks. They could convert it into effective decisions. The system amplified capability that was already present.

For struggling entrepreneurs, the trajectory bent differently. They understood the messages and trusted the tool, but lacked the knowledge scaffolding to discern good advice from poor advice. They used AI for the hardest, most constrained problems where even accurate guidance is difficult to implement. The information did not translate into usable knowledge or viable action, and outcomes turned negative. The model did not fail; the inflection points did.

Not an Isolated Story

These inflection points shape outcomes far beyond business support. They appear across sectors, institutions, and technologies, and they determine whether AI systems produce meaningful benefits, generate muted results, or harmful outcomes.

In India, researchers partnered with a state government to develop a machine-learning tool designed to flag “bogus firms” exploiting the Value Added Tax (VAT) system (Barwahwala et al. 2024). Firms self-declared input tax credits, allowing fictitious entities to overreport input costs and reduce their tax liability. The model performed well and was more accurate than the department’s existing methods. Yet cancellations of bogus firms did not improve. The problem lay at the opportunity conversion inflection point. The tax department lacked the institutional capacity, cross-jurisdictional coordination, and enforcement mechanisms needed to convert their findings into action. The information was accurate, but the structural conditions prevented action.

In 2025, Penda Health, in a collaboration with Open AI, introduced an AI-assisted clinical decision-support tool across fifteen primary-care clinics in Nairobi County (Korom et al. 2025; OpenAI 2025). The system produced high-quality diagnostic alerts, but clinicians largely ignored them and outcomes did not improve. The failure did not stem from model capability. It emerged from a set of inflection points that tilted in the wrong direction. Clinicians were unsure how and when to engage with the tool, trust was uneven, and workflows made it difficult to act on the alerts. After diagnosing the issue, Penda implemented targeted changes: strengthening access and interaction through clearer protocols, reinforcing legitimacy through peer champions, and redesigning workflows so clinicians could reliably act on alerts (opportunity conversion). Once these inflection points were strengthened, the system began to produce measurable improvements.

A similar pattern appears in Google’s flood-alert system in rural Bihar (Jagnani & Pande 2024). The models produced accurate two-to-four-day flood warnings, but these did not reliably translate into action. Many households kept location services off, and only about half of smartphone users could access the alerts. Comprehension and legitimacy inflection points were weak: some alerts were unclear, and trust in digital warnings was uneven. Researchers tested a simple intervention in which community volunteers were trained to interpret the alerts and relay them through loudspeakers and WhatsApp. Villages receiving both AI alerts and volunteer dissemination were 89 percent more likely to trust the warnings and spent 33 percent less on flood-related medical treatment. The intervention facilitated access and interaction (people reliably received the warnings) and a positive legitimacy evaluation (trusted local messengers), allowing accurate information to be converted into protective action.

Across these cases, the pattern is consistent. Technical performance sets the starting point. The inflection points determine the outcomes. When those points aligned with users’ real conditions, interventions gained momentum. When they failed to align, even high-quality models produced limited or negative effects.

Understanding and Applying the Inflection Points

Successfully navigating the model–practice gap is not the only determinant of impact, but overlooking it almost guarantees uneven or disappointing results. This pattern has appeared across decades of ICT for development. What AI deployments need is not just sensitivity to local conditions, but a clearer understanding of the specific inflection processes that shape how potential becomes practice.

Generalizable theory and measurement. These inflection processes recur across sectors, countries, and user groups. They are not one-off quirks of individual interventions but observable mechanisms that shape how people encounter, interpret, and act on AI-generated information. Incorporating them directly into research and evaluation allows teams to compare across contexts, track how trajectories shift for different users, and identify the points where interventions begin to diverge. This lens becomes essential once evaluation moves from model-level and product-level assessments to user-level and impact evaluations (Chia et al. 2025). It shifts attention from average effects to the subgroup dynamics where causal mechanisms actually operate. In almost every example, the crucial question is not whether an intervention “worked,” but for whom, in what ways, and through which inflection points.

Design. A sharper grasp of these inflection points is directly applicable to design and implementation. AI-for-development projects often begin with model development and performance testing, but they cannot end there. Theories of change should articulate how different users will move through these inflection processes, and what institutional, cognitive, social, and material supports are needed along the way. Not every breakdown can be predicted, but the examples from Kenya, the VAT system in India, Penda Health, and the Bihar flood alerts show a consistent pattern. Technical performance establishes possibility. Impact emerges only when the surrounding conditions enable users to pass through the inflection points in ways that convert that possibility into action.

Taken together, the cases show how real-world outcomes are shaped through these inflection processes. When they align with users’ capabilities, constraints, and lived realities, the same system can lift incomes, strengthen clinical decisions, or improve disaster preparedness. When they do not align, even accurate and well-designed systems can lose momentum or slip into harmful territory. Designing, evaluating, and governing AI for development therefore requires systematic attention to these inflection points, because they determine the direction, magnitude, and distribution of impact.

References

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). (2019, December). Supporting firm growth through consulting and business training. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/policy-insight/supporting-firm-growth-through-consulting-and-business-training

Akrich, M. (1992). The de-scription of technical objects. In W. E. Bijker & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology/building society: Studies in sociotechnical change (pp. 205–224). MIT Press.

Anderson, C., Robbey, D. (2017). Affordance Potency: Explaining the actualization of technology affordances. Information and Organization, 27(2): 100-115.

Angwin, J., Larson, J., Mattu, S., & Kirchner, L. (2016). Machine bias. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

Avgerou, C. (2010). Discourses on ICT and development. Information Technologies & International Development, 6(3), 1–18.

Barwahwala, T., Mahajan, A., Mittal, S., & Reich, O. (2024). Using machine learning to catch bogus firms: A field evaluation of a machine-learning model to catch bogus firms. ACM Journal on Computing and Sustainable Societies, 2(3), Article 30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3676188

Chia, H. S., Carter, S., Abrol, F., Madon, T., On, R., Walsh, J., & Wu, Z. (2025, April 16). An AI evaluation framework for the development sector. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/ai-evaluation-framework-for-the-development-sector

Ciborra, C. U. (1999). Notes on improvisation and time in organizations. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 9(2), 77–94.

Ciborra, C. U. (2002). The labyrinths of information: Challenging the wisdom of systems. Oxford University Press.

Deloitte. (2025). AI ROI: The paradox of rising investment and elusive returns. Deloitte. https://www.deloitte.com/nl/en/issues/generative-ai/ai-roi-the-paradox-of-rising-investment-and-elusive-returns.html

Gaver, W. W. (1991). Technology affordances. In CHI ’91: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 79–84). ACM Press.

Gebru, T., et al. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? FAccT Conference. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

Heeks, R. (2002). Information systems and developing countries: Failure, success, and local improvisations. The Information Society, 18(2), 101–112.

Jagnani, M., & Pande, R. (2024, April 3). Forecasting fate: Experimental evaluation of a flood early-warning system. https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/campuspress.yale.edu/dist/7/2986/files/2024/04/Google_Floods-bcdf49042e23059a.pdf

Korom, R., Kiptinness, S., Adan, N., Said, K., Ithuli, C., Rotich, O., Kimani, B., King’ori, I., Kamau, S., Atemba, E., Aden, M., Bowman, P., Sharman, M., Hicks, R. S., Distler, R., Heidecke, J., Arora, R. K., & Singhal, K. (2025). AI-based clinical decision support for primary care: A real-world study. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.16947

MacKenzie, D., & Wajcman, J. (Eds.). (1985). The social shaping of technology. Open University Press.

Madon, S. (2000). The internet and socio-economic development: Exploring the interaction. Information Technology & People, 13(2), 85–101.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). The state of AI: Global survey 2025. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai

MIT. (2025). The GenAI divide: State of AI in business 2025 (v0.1) [Report]. https://mlq.ai/media/quarterly_decks/v0.1_State_of_AI_in_Business_2025_Report.pdf

Narayanan, A., & Kapoor, S. (2024). AI Snake Oil: What Artificial Intelligence Can Do, What It Can’t, and How to Tell the Difference. Princeton University Press.

Narayanan, A., & Kapoor, S. (2025, April 15). AI as normal technology: An alternative to the vision of AI as a potential superintelligence. Knight First Amendment Institute. https://knightcolumbia.org/content/ai-as-normal-technology

OpenAI. (2025, July 22). Pioneering an AI clinical copilot with Penda Health. https://openai.com/index/ai-clinical-copilot-penda-health/

Orlikowski, W. J. (2000). Using technology and constituting structures: A practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organization Science, 11(4), 404–428.

Pinch, T. J., & Bijker, W. E. (1984). The social construction of facts and artefacts: Or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. Social Studies of Science, 14(3), 399–441.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of human–machine communication. Cambridge University Press.

Toyama, K. (2011). Technology as amplifier in international development. Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, 75-82. https://doi.org/10.1145/1940761.1940772