Introducing Ideas from the Palaver Tree: The Necessity of African Pedagogies on Artificial Intelligence

Digital technologies, particularly those as pervasive as artificial intelligence (AI), raise critical questions about how such innovations are studied and who participates in their meaning and knowledge making. The very conception of AI and its advancement as a frontier technology is rooted in perceptions of ‘intelligence’ as expertise that can be economised and efforts to wield knowledge politics for the purposes of empire-building. This colonial legacy has subjected Africans to an extractivist, hegemonic global knowledge economy. To ensure that neo-colonialism is not further embedded into the material-to-digital continuum, we must create spaces where AI is defined and challenged by African perspectives.

The Global Center on AI Governance (GCG) courses have been an exploratory exercise for how such complex topics can be discussed in relation to diverse sociocultural realities, within our natural and digital realms, both within and beyond the continent.

Ideas from the Palaver Tree is a collection of analytical articles wherein GCG alumni engage with inquiries that emerge in such a virtual learning environment. This inaugural collection is a testament to the value of fostering spaces for collective decolonial inquiry about AI.

Carving Out a Decolonial Digital Learning Environment

The Dartmouth Summer Research Project, where the term Artificial Intelligence itself was coined in 1956 was attended by a small group of white male academics, many of whom were mathematicians, engineers and computer scientists. The meeting took place in an elite Western university, and was made possible by a private philanthropic organisation that took a ‘modest gamble’ on the new field. Thus, the foundational ideas of AI emerged within a historical context where those with social privileges and institutional access pursued the simulation of human intelligence through identifiable patterns as a valuable intellectual endeavour. While participation in AI research has diversified beyond computer science since, there remains an imbalance in the epistemic authority across fields and lack of diverse regional perspectives within the discourse.

AI funding has also experienced a steady increase in the past decade, with global corporate AI investment surging to $252.3 billion in 2024 of which 44.5% is private investment. However, these investments remain unevenly distributed with Africa estimated to have received less than 1% of global AI funding in the second quarter of 2024.

AI research is increasingly shifting away from academia toward industry, driven by their access to vast amounts of data and immense computing capacity. These resources understandably attract a significant majority of scholars, with 70% of those with a PhD in artificial intelligence getting jobs in private industry. The academia-to-industry migration has in turn led to greater industry influence in AI research, with over a third of papers at leading AI conferences now including one or more industry co-authors. This trend shapes the trajectory of knowledge production in the emerging field, raising concerns about how the prioritisation of rapid innovation for market profit could compromise on the critical inquiry into the associated risks.

Conversely, pluralistic knowledge-making processes invite us to parse through our tangled webs of ideas, diverse experiences, and varying priorities to ignite epistemic conduits that facilitate new understandings and re-imaginations of AI . Such approaches would require time and resource investment in spaces that are not primarily motivated by monetary priorities; where academics, practitioners and policy experts and advocates can convene to envision the role of AI in our collective futures, and which parts of our social livelihoods should be exempt from automation.

The Importance of African AI Discourse

In the African context, establishing forums for situated AI discourse is critical, because the history of knowledge politics, particularly with regard to technology as a driver of progress, is mired in a history of material dispossession, knowledge reappropriation and disregard for Indigenous value systems. These dynamics are rooted in the notion that disciplines deemed economically lucrative should be prioritised over ways of knowing that consider human beings as not only living within nature but also part of, and in turn responsible for all of our relations. Colonial convictions that we must extract the earth for all its wealth have led us to wield digital technologies driven by extractivist practices, rather than a reciprocal relationship with the land and water that sustain us.

Understanding AI from a specifically African perspective is not important merely because of an essential difference. As Tania Murray Li highlights in The Will to Improve, communities’ conditions must be understood in relation to political and economic forces, otherwise, we risk oversimplifying historically rooted, complex and contested practices, perpetuating deficiency narratives, and thereby justifying the need for external “improvement”. Our intention with inviting African viewpoints from the epistemic margins to the centre of the responsible AI field is for a deeper exploration of how those still grappling with unequal global power structures are contending with the rise of new empires of AI. A key objective here is to scrutinize the promises that AI will address persistent socioeconomic issues, especially in Africa. Those living and working on the continent have a right to interrogate how their land, labour, and surrounding waters are being used for AI-driven development initiatives.

Esther Mwema and Abeba Birhane have illustrated how the undersea cable projects surrounding Africa, owned by Western big-tech corporations, parallel the historical routes of the transatlantic slave trade. These internet infrastructures, which connect the continent to the rest of the world, effectively transpose colonial legacies of expansionism. Their critical cartography elucidates how the same pathways that facilitated some of the most egregious harms in history, whose ripple effects are still felt today, could now be used to encode and streamline African realities into data for financial domination. Therefore the pursuit of African digital sovereignty extends beyond the Westphalian understanding, toward claiming authority and responsibility over the resources and narratives of African digital commons.

AI Pedagogy Rooted in Africa

GCG has collaborated with university partners to undertake the important task of developing AI ethics, policy and human rights courses that are rooted in Africa and globally informed. We acknowledge the crucial challenge before the continent, as highlighted by Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, to decolonise the concept of the university from merely a "university in Africa" into an "African university”, a site for pluralistic epistemologies toward cognitive and social justice for all. We also appreciate how universities on the continent have been spaces of struggle for Africanisation and decolonisation. We hope to contribute to these efforts by designing AI courses framed by African pedagogies that are often missing from the dominant discourse.

Engaging with decolonial scholarship sparks inquiries often overlooked in conventional AI discourse. As one of our collaborators for the AI, Ethics and Policy in Africa course, Jake Okechukwu Effoduh, rightfully pointed out in a particularly memorable seminar session, “sometimes the best AI is no AI”. Such provocations arise when we engage in discussions that are informed by the continuity of exploitative systems, and strive to change them for the better. When we speak of African perspectives, we refer not only to the knowledge emerging from the continent, but to ways of knowing that bear witness to technology-enabled injustices, and are yet optimistic about imagining alternatives for socially-driven technological development.

Achille Mbembe encourages us to grapple with the dialectics of what he has called ‘planetary entanglement’ and enclosure or containment, shaped in large part by tech giants. Our discussions about AI in Africa must therefore be Afropolitan, which involves engaging with the global historical, political, and socio-cultural influences that shape African societies, while resisting the forces that seek to confine the continent as an other than the world. To this end, GCG courses are facilitated and attended by folks living in Africa and those elsewhere in the world who share the conviction that understanding the African ethics, rights, concerns and priorities in the face of AI, is an important element of the global discourse of responsible AI.

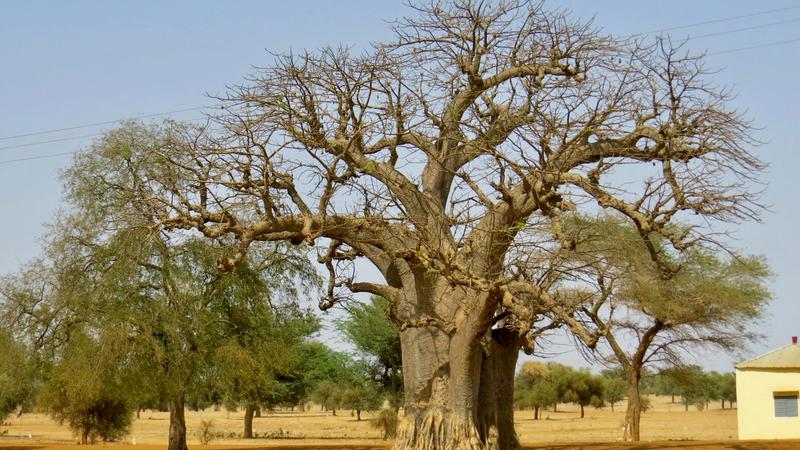

Ideas from the Palaver Tree

Over the past year, our discussions among GCG course facilitators and participants have mirrored the longstanding custom of the palaver tree, where African communities gather to deliberate and exchange ideas. We hope to extend the knowledge created, curated and challenged in these virtual rooms to a wider audience.

We invite you to learn from, connect with, and even challenge the ideas presented in this collection, affirming the continuous and kaleidoscopic nature of African pedagogies.

Articles in the Ideas from the Palaver Tree collection

- Listening to the Body: Responsible AI and Public Health in Africa by Gabriela Carolus

- How Can African Countries Tackle the Emerging Threat of AI-generated or Manipulated Mis-and Dis-information in the Context of Elections? by Andreas Fransson

- AI in Social Sciences: How Large Language Models are Reshaping Text Analysis by Fátima Ávila Acosta

- AI, Care Work, and the Politics of Value by Jess-Capstick Dale

- Epistemologies and Political Economies of AI in Africa and the World by Thomas Linder

- Responsible AI Beyond the Global North by Alice Liu

----------------

Articles in the “Ideas from the Palaver Tree” collection were co-edited by Selamawit Engida Abdella and Dr. Fola Adeleke