World Day for International Justice: Assessing Responsibility & Accountability in AI

NewsToday, as we mark 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝 𝐃𝐚𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐉𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐞, a crucial question echoes in the AI landscape: When AI goes wrong, who is truly accountable?

As the Global Index on Responsible AI, under the dimension of Responsible AI Governance, we've measured accountability as a core AI Principle. This concerns humans or decision-making bodies being responsible for outcomes and providing justifications for AI's design, development, and deployment.

Despite the unique ambiguities and challenges that AI technologies present, it is important to create mechanisms for responsibility and accountability in order to mitigate the risk of harm and to uphold the promise and potential of trustworthy AI

Below are the highlights from our analysis:

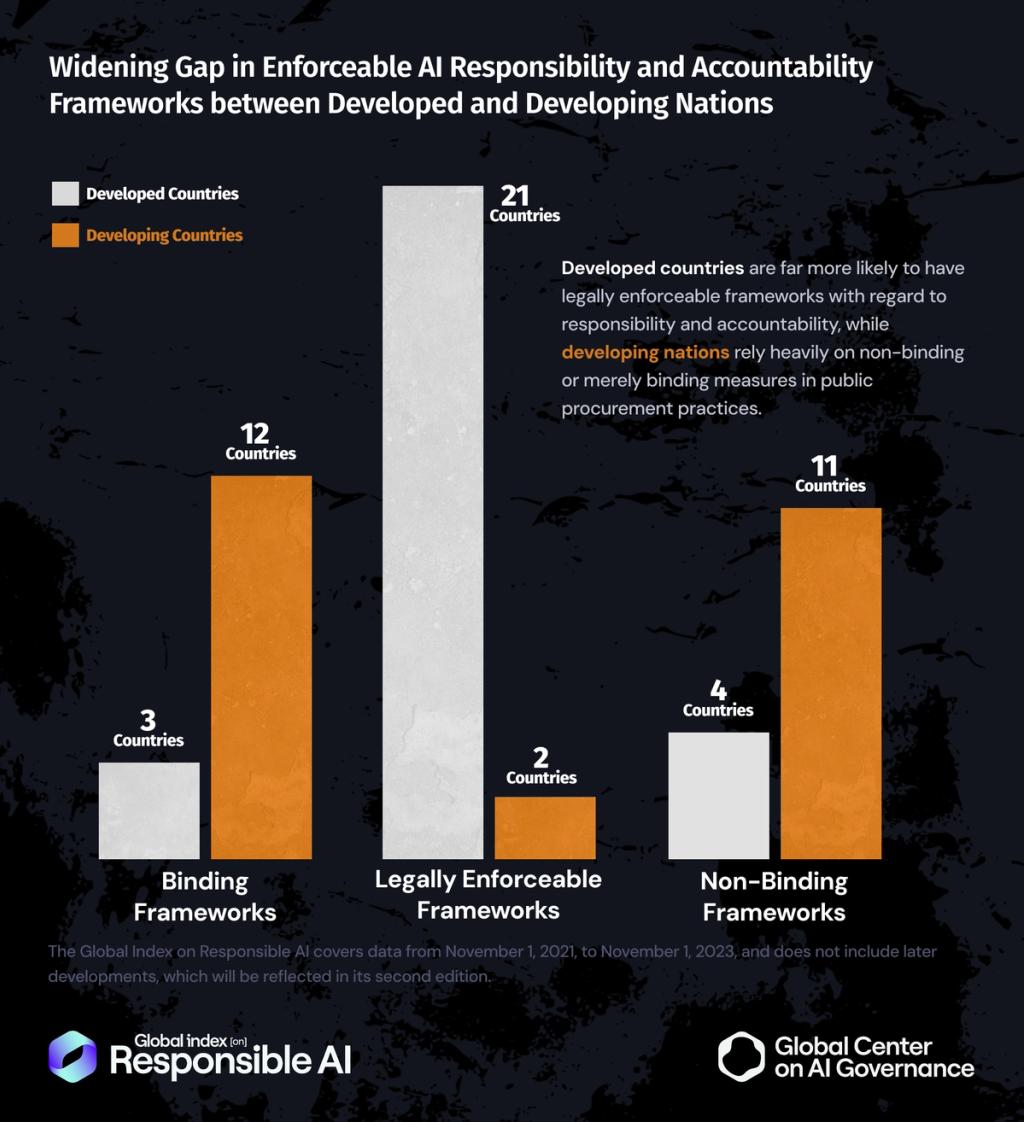

Chart 1

There’s a significant gap between developed and developing countries when it comes to responsibility and accountability in the use and development of AI systems. Among developed nations, 21 countries, mostly in Europe, have instituted legally enforceable frameworks to ensure responsibility and accountability in AI, signaling a robust commitment to ensure makers and users of AI systems are answerable, accountable, and responsible for their actions. Meanwhile, only 2 developing countries Georgia and the Philippines have evidence of legally enforceable frameworks. Developing nations make up a majority in the binding (12 countries) and non-binding (11 countries) framework categories, which often lack the legal teeth necessary to ensure long-term compliance and protection for citizens.

Note: For analytical purposes, countries are grouped into develop / developing regions as defined by the UNDP Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use of the United Nations. It is important to note that Kosovo and Taiwan are not part of this classification; for the purpose of this analysis, they have been included in Europe and Asia, respectively.

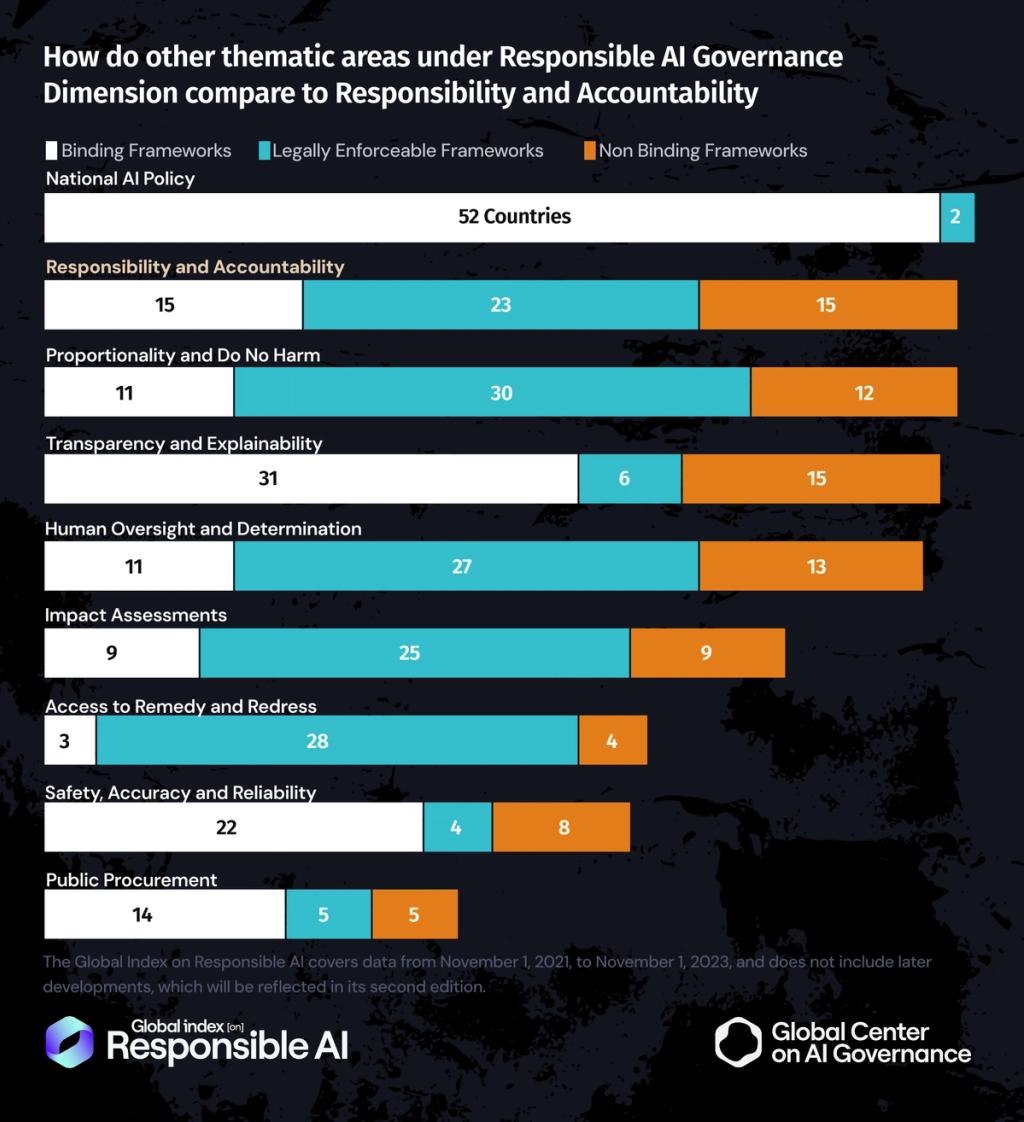

Chart 2

Responsibility and Accountability is one of nine thematic areas under the Responsible AI Governance dimension, which assesses how effectively countries embed rights-based and effective AI practices. Compared to the other areas, Responsibility and Accountability presents a mixed picture. It ranks high in terms of the number of countries with legally enforceable frameworks (23), but it falls behind in binding frameworks (15), significantly trailing National AI Policy (52) and Transparency and Explainability (31). Similar patterns appear in areas like Proportionality and Do No Harm and Human Oversight, which show strong legal enforceability but limited binding commitments. In contrast, National AI Policy leads in binding frameworks, while Access to Remedy and Redress ranks highest in legal enforceability. Responsibility and Accountability therefore sits in the middle of the pack performing moderately well on enforceability, yet clearly lacking in government-level binding commitments.

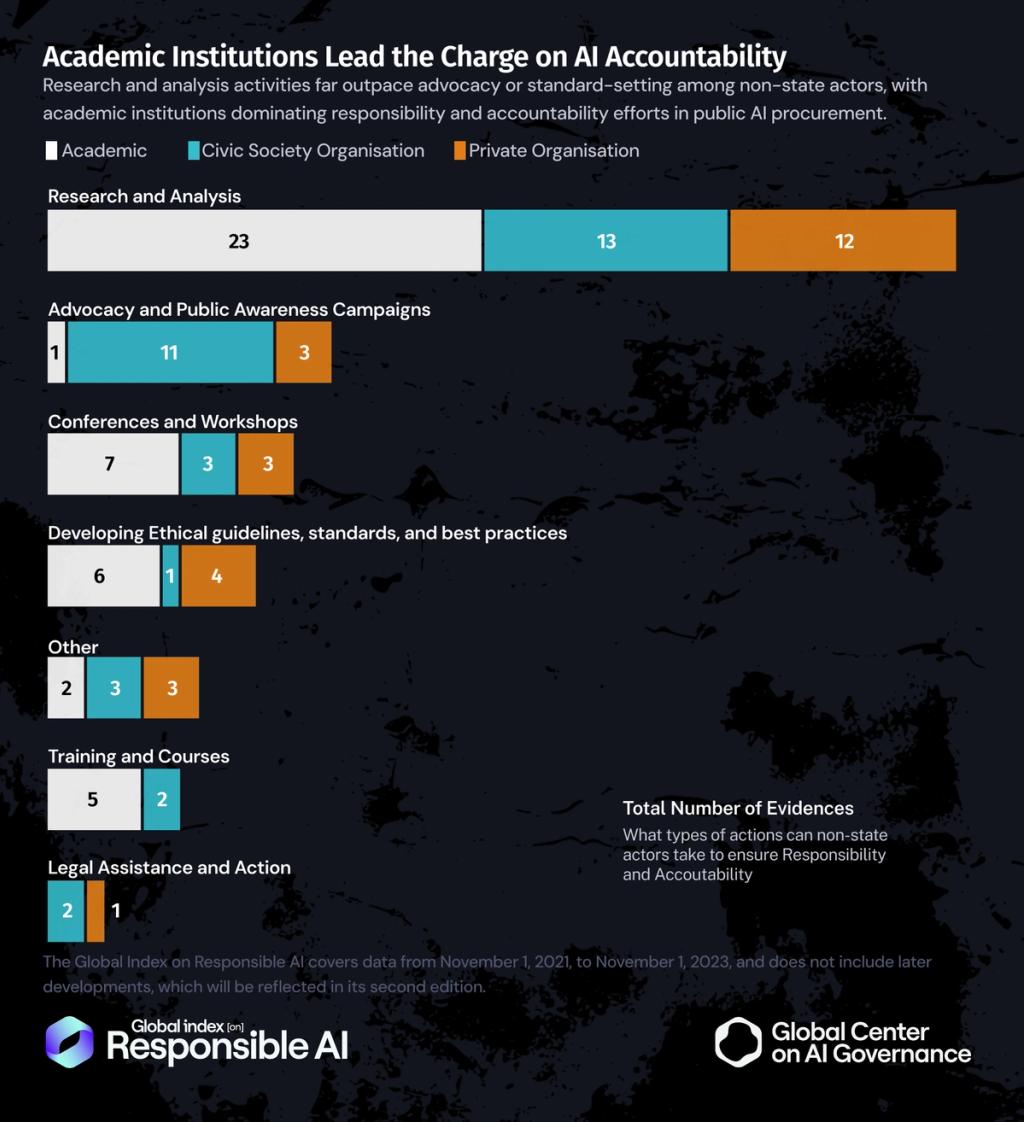

Chart 3

Academic institutions lead among non-state actors in the domain of research and analysis, which is unsurprising given their foundational role in producing research, advancing knowledge, and guiding evidence-based decision-making. This activity is evidenced in 23 countries, more than double the presence recorded in the civic society space and private sector terrain, which report 13 and 12 activities, respectively.

Civic society organizations, on the other hand, have carved out a noticeably strong presence in advocacy and public awareness campaigns. This is an expected but critical function, allowing them to outpace both academics and private actors while acting as the sector’s public conscience. Meanwhile, private organizations contribute primarily through the development of ethical guidelines and best practices, playing an important role in norm setting and operational governance.

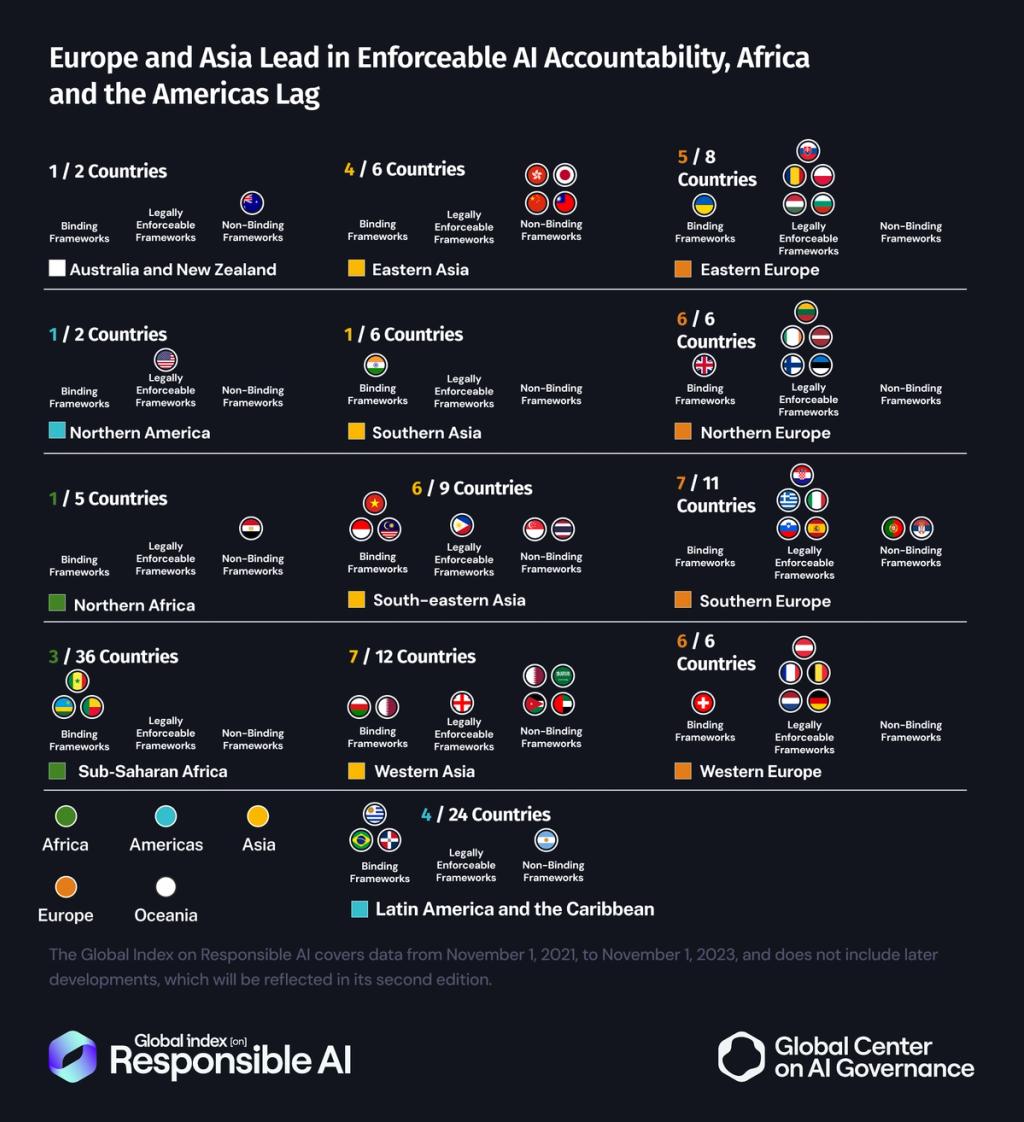

Chart 4

Across Europe, both North and South, the presence of multiple legally enforceable frameworks is clear. Countries from Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western Europe each report at least five such frameworks, along with several binding arrangements. This points to an advanced policy environment that compels governments and vendors to uphold AI responsibility standards.

Similarly, Asian sub-regions such as Eastern Asia, Southeastern Asia, and Western Asia demonstrate leadership in this sphere. In stark contrast, all six Central Asian countries Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan show no evidence of any government framework to ensure responsibility and accountability in the procurement of AI systems. A similar pattern is seen in Southern Asia, where only India has a binding framework, while the remaining six countries in the sub-region lack any such enforceable mechanisms.

Across the Global South, enforceable government-led accountability frameworks for AI remain largely absent, particularly in Africa and the Americas. Sub-Saharan Africa, Northern Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean offer only a handful of binding or non-binding frameworks. Among them, only Latin America stands out, with three binding frameworks and one non-binding arrangement.

Chart 5

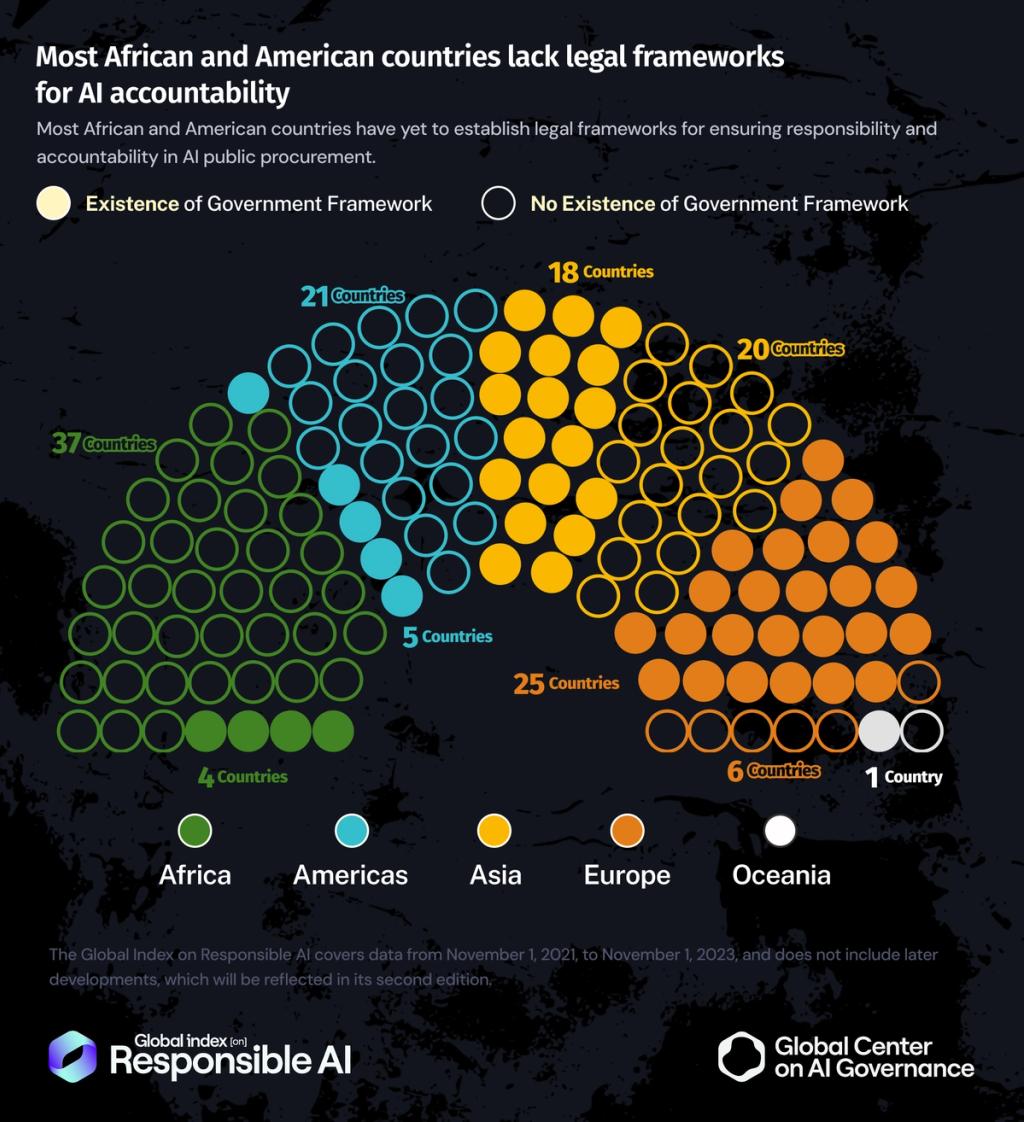

There’s a continent-wide blind spot across Africa and the Americas regarding the regulatory presence needed to ensure responsibility and accountability in the use and development of AI systems. Africa, for example, demonstrates a worrying gap: only 4 out of 41 countries have frameworks in place, while 37 have no evidence of such measures. The Americas fare only slightly better, with 5 countries out of 26 having existing frameworks. This sharp divide highlights not just regional variation but an urgent global imperative: most regions, except Europe, have yet to fully embrace public sector responsibility and accountability in AI, raising significant questions about preparedness for ethical and transparent AI governance.

View the full analysis on Responsibility and Accountability here: https://www.global-index.ai/thematic-areas-Responsibility-and-Accountability

Data Visualisation Credit: Jayeola Gbenga